Why Astrobiology Matters: A Roundtable Discussion

Written by Harvey Sapigao and featuring commentary from Dr. Anamaria Berea, Priya DasSarma, Anurup Mohanty, and Sibsankar Palit. Harvey completed this work as part of a final project for the Young Scientist Program at the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science.

In one of the episodes of the BMSIS podcast, Drs. Sanjoy Som and Jacob Haqq-Misra talked about the reasons why we explore space, presumably over some beers (the podcast is named Beer with BMSIS). Just a few minutes in, they get to the heart of the discussion; Dr. Som recalls the conversation with one of his friends about the motivations behind space exploration. Instead of listing run-of-the-mill reasons, he let his friend imagine a world where humans are not interested in looking up at the stars. “It ended up coming to the conclusion that it would be inherently unhuman to not wonder and seek to understand the unknown,” he said.

The episode covered a wide range of topics, from the different values derived from space exploration, to its philosophical, ethical, and theological considerations, to the possibility of leaving Earth for survival. But I wanted to delve deeper into the more nuanced question of why astrobiology matters specifically. So in an attempt to add to the conversation, I gathered four BMSIS people from different walks of life for a (Slack) roundtable discussion.

Panelists

Anamaria Berea, PhD is a Research Investigator and YSP Mentor focused on economics, data science, and astrobiology.

Priya DasSarma is the BMSIS Representative to the Board of Directors at BMS and a YSP mentor with a project entitled “Evolution and Survival of Ancient Microbes – A Bioinformatic Approach.”

Anurup Mohanty is a Visiting Scholar and also a 2020 YSP graduate with a project entitled “Amino Acid Abundance Pattern as a biosignature, contributing to the online repository with scientific literature & pieces of evidence.”

Sibsankar Palit is a YSP Research Associate with a project entitled “The Life Detection Knowledge Base: Research on Biosignatures” under Dr. Graham Lau.

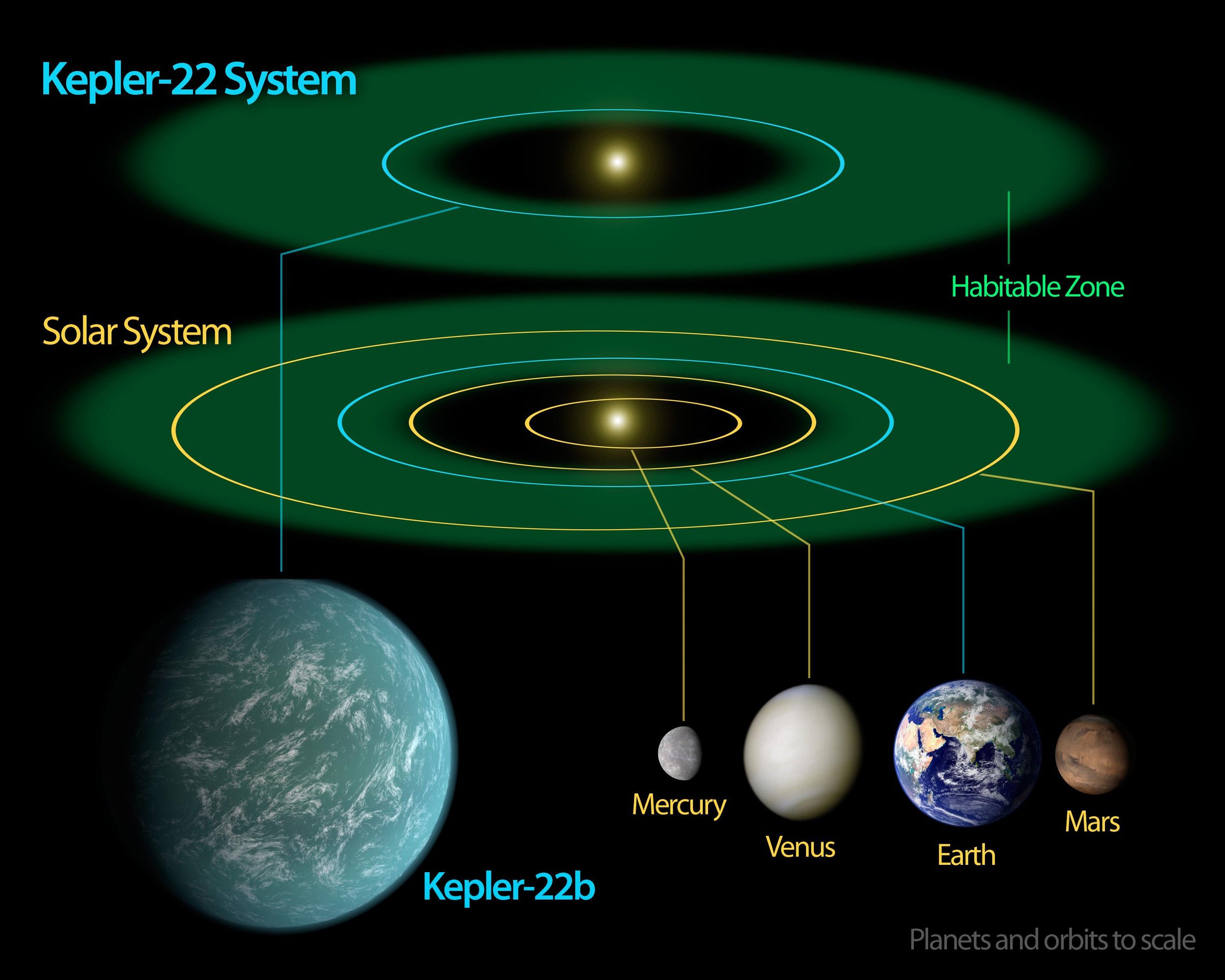

Harvey Sapigao: I’d like to preface this conversation by recalling the time when I was watching news on our old static TV about a decade ago. At the top of the hour, they reported a new exoplanet that can potentially harbor life. At the time, I didn’t know Kepler was a telescope; I thought it was the name of the exoplanet (it was in fact called Kepler-22b). I remember being so amazed and excited at that time that I couldn’t forget the image they flashed on screen, even though it’s barely distinguishable with our terrible reception. To this day, I still vividly remember the image, which is the one attached below.

Kepler-22b and the Habitable Zone (image credit: NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech)

The next day, I was walking home with my friends after school, and I just kept staring at the clear sky, imagining what kinds of life are out there and all the possibilities that the universe could offer. I’d say that that news was one of the most impactful moments of my life which fostered my interest in space and life outside Earth.

I’m curious: Do you have similar stories that influenced your career path or that had a great impact in your interests in astrobiology now?

Priya DasSarma: Well, going back many decades, the year I was born, my parents took me out into their garden and held me up to the sky as the BBC World Service Shortwave radio broadcast the US landing on the Moon – Chandramā, as we call it in India. I knew that there was supposed to be much up there, beyond what we could see, but the moon was the only heavenly body I could see. So I guess I was born at a time when space was a mystery that was being solved. Many different things happened along the way, too complicated for this forum, and I was working with Haloarchaea – microbes that could potentially survive Martian conditions, and that use phototrophy to generate energy from the sun – and I thought that the concept of astrobiology was really a very hard one to grasp, given that the only life we have discovered is that on our own planet, and that we have not fully defined life in a universal sense. On this planet, Prof. Har Gobind Khorana and others won the Nobel Prize cracking the genetic code, which has turned out to be the universal code to life on Earth.

Yesterday (August 23), India's Chandrayaan-3 (“moon craft” in Sanskrit) mission landed on the South side of the Moon, and I gathered my family (virtually) to watch, with anticipation and pride, the successful landing. I guess space (in which we all live, right? since Earth is in space) has been in my life all the while.

Harvey Sapigao: That’s a cool story. Your parents took you to the garden to watch the moon landing, and now you gathered your family to watch another moon landing. It’s a full-circle moment.

Anamaria Berea: I've always liked science and wanted to become a scientist since I was very little. I was not specific about any kind of science, because I liked them all, from physics and biology to social science. I've always been really good at math, but I also liked the arts and languages. I became an interdisciplinary scientist and I am more focused on methods and techniques that I can apply to a wide range of phenomena. As an undergrad I became fascinated with the idea of complex systems. For a long time, though, I studied economics. I enjoyed the counterintuitive logic and math in economics. I came to discover astrobiology only after I finished my PhD and I really like the interdisciplinarity aspect of it and that I can apply everything I learned elsewhere over here.

Harvey Sapigao: From the conversations I had with BMSIS folks so far, almost all have a wide range of interests. I guess that’s one of the prerequisites of astrobiology, because it is, as you said, interdisciplinary.

Sibsankar Palit: Indeed. Such beauty is our universe that it cannot be understood by separating it into different fields. It can be best understood in its inter-, intra-, multi-, and trans-disciplinarity and astrobiology satisfies it all!

Since my secondary school days, I kind of had an infatuation with chemistry whilst my friends were more into physics and biology. They literally hated chemistry and I embraced it. I had a small lab at my home as well in Siliguri, West Bengal, India (my hometown).

Whilst in high school ready to pursue a career in pharmacy after +2 (equivalent to High School in India), it was during the COVID-19 lockdown that I gained more clarity, and now am pursuing a degree in chemistry. I was very much inspired by the storyline of the 3rd episode of the Cosmos:Possible Worlds documentary, (the episode is entitled Lost City of Life) where I was introduced to astrobiology and also thought about the very central role of chemistry in this field. I was hooked on space!

The story of the Father of Modern Cosmochemistry, Victor Goldschmidt, literally inspired me. He studied physics, chemistry, geology, and biology at the same time in his undergraduate years and attained a professorship without any professional training. He made a geology version of the periodic table which explains how the basic elements formed complex minerals here on Earth. That time, I literally had wild thoughts if we could also have a biology periodic table as well where we can fit all kinds of life in the universe! Goldschmidt went on to work on olivine, one of the foremost minerals to have contributed to the origin of life on Earth, and published many works based on his study during his lifetime. He openly declared himself Jewish during Hitler's rule and even fled his trap by fooling his army personnel using science as he knew the details (science can save your life as well).

Coming back to my story, slowly I began networking with similar individuals on LinkedIn. I got to know about unique fields in space like space biology, space architecture, and space sociology, and gained greater clarity about the role of chemistry in space. From astrochemistry/cosmochemistry to systems and prebiotic chemistry to space food, materials, and astronaut suits, chemistry is everywhere!

Thus I concluded: chemistry was born in space and we certainly need chemistry to both save and move beyond Earth!

Anurup Mohanty: I was never actively into space sciences as a kid, but I loved biology. Probably because of the awesome morning walks with my father (who holds a master's in horticulture). Looking at plants, recognising them from their leaves and branching patterns and witnessing bees pollinate were some of the highlights.

Various interests led me towards a bachelor's degree in biotechnology. My university had a very engineering focused curriculum and hence there were student-led teams that made race cars, copters, robots and much more. I saw a poster of an analogue Mars rover team, called Rudra, which happened to be the only team that recruited people from bioengineering. I had to apply, and fortunately made it into the team. That was my first exposure to astrobiology and biosignatures. I read papers and worked on the payloads for the rover just because it was fun. The BMSIS YSP happened and I realized that this stuff that I enjoy is a very viable career option. A few projects and Carl Sagan books later, I found myself actively pursuing this field, and I start my PhD next month!

Harvey Sapigao: How does your interest in astrobiology influence your worldview, philosophies, and religious beliefs?

Priya DasSarma: As a child of this planet, who feels that things are interconnected and believes in the butterfly effect, I think it is a natural thought to believe that possibly there is life out there — hence, there may be a field of astrobiology. I think it is humbling to think of this Pale Blue Dot (1990) and the fragility of its inhabitants. Astrobiology reinforces this thought. So the view of this world is from "away" — and with affection and worry. We MUST use our collective knowledge, power and connections to protect the environment. On the other hand, working with a microbe that is so hardy and amazing and that could become a space traveler is awe-inspiring and really interesting! When our laboratory first sequenced the genome (the first ever haloarchaeal genome in 2000, and one of the first genomes ever), Prof. DasSarma was interviewed and said this "could be one day used to develop vaccines and produce useful proteins such as antibiotics as well as for space research, could contribute to an understanding of how life arose on Earth or help scientists recognize evidence of life on other planets in our solar system,” stating that “What is neat about that is that it expands our notions of what life is.” And history has proven that true; We have had success in the development of vaccines and drug-delivery systems as well as have seen the Purple Earth Hypothesis develop and the membrane be considered a biomarker in exoplanet searches and so much more.

Sibsankar Palit: For me, the very words of Sagan "The cosmos is also within us. We are made up of starstuff. We are a way for the Cosmos to know itself!" are by far the most philosophical and poetic words in complete alignment with reality and helped influence my worldview, philosophies, and religious beliefs that I currently hold. So insightful and beautiful are the words that it pretty much sums up everything from our origins, to our current state and our fate in the Universe. We as a collection of atoms are put exactly in the way that makes us alive such that we can evolve and be intelligent enough to even comprehend the vastness of the universe and return back to the stars through space exploration (the place we originated as atoms). Isn't it so beautiful? So trivial are the wars and our worldly wants in front of this saga that made us and the current moment possible. It truly fills me with humility and a sense of responsibility towards each other and myself to learn from the past and do our best every moment and every day to make a better tomorrow!

Harvey Sapigao: That’s a great quote from Sagan. Would you consider yourself a religious person or not? And have these beliefs affected your path as an aspiring scientist?

Sibsankar Palit: To answer this first we need to define what religion is? If you say it's about a community sharing certain characteristics or traditions or other, then certainly by birth I am a Hindu and have been brought up accordingly. But then if you say it's about a belief system in one or more GODs (Generator/s, Operator/s, and/or Destroyers) of the universe then I am an agnostic atheist. I don't know whether they exist and at the same time also don't approve of the points in the different religious texts about them that do not match with scientific evidence. To me, science is a continuous quest to know about the universal mysteries (or as may be called as the GOD's mind).

I like Einstein's reply when he was asked about his belief in GOD. He said, "I believe in Spinoza's God!". Spinoza said, "Natura Naturans" or can be implied as God didn't make Nature, God is Nature itself.

In a nutshell, I am a secular and democratic humanitarian, open and tolerant to perspectives and systems until and unless anything harms anyone unnecessarily or for gain. Fortunately, I take science and education as a way of liberation that harmonizes with my beliefs as well!

Harvey Sapigao: Thank you for the distinction. That’s a great way to put it.

Anurup Mohanty: I am a preacher of "doing science for the sake of doing science." A textile worker who wanted to use good lenses to examine fabric happened to look at pond water, just out of curiosity and we got an entirely new field of research: microbiology. Thanks Leeuwenhoek!

We must also thank Fleming for noticing the plate that gave the world antibiotics. There are many examples. I think astrobiology being a recent research field is at a fundamental stage. There are a lot of "whys".

But eventually, just like medicine, which hosts questions like: how do we target cancer cells? Or how do we deal with antibiotic resistance? Things will become more problem/question-oriented in astrobiology. But till then, I think it's best to enjoy spin-off technologies and accidental breakthroughs.

Harvey Sapigao: Oh wow. I didn’t know that’s how microbiology started. I like your philosophy, which puts purpose and utility as secondary as opposed to the main driving factor. Frankly, in our generally capitalist world, we put too much focus on the practicality and immediate benefits of all the things we do, and we forget that there’s so much more we can get beyond material things.

Still, many people believe that there are other pressing issues that deserve more public funding than astrobiology. I’d like to ask the table: In your opinion, what is the most compelling reason why humanity should invest resources and effort into the field of astrobiology?

Sibsankar Palit: There are and can be many utilities of astrobiology research/study. The other day, as a part of a session, NASA postdoctoral scholar, Dr. Bonnie Teece, very beautifully mentioned that there have been studies done at NASA where some people who went on to teach about astrobiology to many prisoners impacted their way of life, and the levels of the crimes they committed decreased. Again, it helps people become aware of climate change and also about the adverse effects that come along with it, be it through data from other planets that were similar to Earth in the past or even studies on Earth. Accordingly, ground steps are taken to reduce climate change. This study also states how the technology for the rapid Covid tests was based on the DNA study of the microbes living in Yellowstone analogs.

But then again, I love that BMSIS also lays emphasis on, "To explore is to be human.” The best part of astrobiology is that it informs, involves, and inspires all at the same time! Astrobiology informs us about our origins, evolution into endless forms and distribution, and the future in the cosmos. Astrobiology involves people from different backgrounds, ages, regions, and sects as it's the quest to know about us. Astrobiology inspires us in our history and the endless endeavor to continue exploration for exploration's sake. Aren't these humans enough for a human to invest in, during one's lifetime?

Priya DasSarma: I think it is important to have folks learn the basics – there is a lot of hand waving and the fundamentals are lost. Should we, as (budding) astrobiologists, be thinking about how to make what we do useful to where we come from? Mother Earth?

Anurup Mohanty: I think we should and we are! PCR comes to mind. Thermophiles could be considered candidates for life on ancient Mars. Studying them has given us PCR.

Similarly, geobiologists are really interested in understanding what lies beneath the surface and how microbes make a living in the depths. We can learn how to do carbon sequestration from the subsurface microbes. I very much agree that we should also actively think about utilizing the knowledge but the joy of discovery shouldn't be lost either.

Priya DasSarma: Oh yes, the Taq story. So, these scientists went to Yellowstone – a famous National Park here in the United States – and they sampled the pools there, and isolated Thermus aquaticus, from which they derived Taq polymerase. Many efforts later and much money made–well, the folks making the enzyme made the money and then... check it out on this website.

(Summary: Bioprospecting is the act of researching to invent products for commercial purposes. One major distinction between bioprospecting and logging and mining is that the former does not directly harvest products from nature. Instead, the products are derived from the discoveries made from researching extremophiles.

Bioprospecting led to the discovery of the Taq polymerase, an enzyme that enabled for cheap reproduction of DNAs, which then led to a wide array of uses such as forensics examination and medical diagnoses. Before the discovery, DNAs cannot be easily replicated in a lab.

Unfortunately, the Taq polymerase has become a lucrative product for companies. From the website: “Companies that sell the Taq enzymes have earned profits, but Yellowstone National Park and the United States public receive no direct benefits even though this commercial product was developed from the study of a Yellowstone microbe.”)

If Mother Earth would be compensated for bioprospecting, or other planets - how would those on the round table feel that would work?

Grand Prismatic Spring, at Yellowstone National Park in the U.S.A. (Image credit: Getty Images)

Harvey Sapigao: I guess the only way to “compensate” Mother Earth for bioprospecting is to preserve the natural habitats, right? I like the fact that bioprospecting is not as destructive as, say, logging and mining, but I wish those companies who made profits off of the Taq enzymes made efforts to provide assistance with preserving US parks or at least donated some of their profits to the parks, or fund other causes such as research projects about bioprospecting.

Priya DasSarma: Absolutely! You got exactly the sentiment!

Harvey Sapigao: Thank you all for the great discussion! I have one final question: If someone asks you “why study astrobiology? What’s the point?” What would you say?

Sibsankar Palit: Firstly, as a counter, one can more fundamentally ask “why even bother to do something/anything when we all know that we all have to die someday or the other?” Right? Nevertheless, coming back to the point: a utilitarian can answer “study astrobiology to get an exciting career (as it is an emerging and important field).” A researcher would answer “to find out more about the mysteries of life in the universe.” I personally would urge people to study astrobiology to become a good citizen. A citizen of the world, A citizen of the universe! On a more philosophical note, think of the hardships the atoms, molecules, cells, and simpler life forms had to go through to initiate and evolve enough to form us so that we can comprehend the beauty of the cosmos. It teaches us about patience and courage. Think how tiny we are with respect to the cosmos and how large we are with respect to the subatomic particles but still, we can comprehend both. Humbling! Astrobiology makes us more responsible and kind towards each other and the environment as well. Astrobiology makes us human!

Anurup Mohanty: We should study astrobiology because we don't know many things about our own planet and the universe we live in. Humans have this innate curiosity to explore the unknowns. That's the reason why our ancestors walked out of Africa, crossed the sea and continents to make us who we are today. For us the sea isn't so difficult, so let's look at the sky.

I would emphasize that astrobiology is more about Earth than it's about space. Because that's the only example of life, and we haven't fully understood our life and its origin.

If we can invest to know about what happened in recorded history, about the civilizations that were spread across continents, why not go back more and learn about how everything started? How microbes ruled the planet for billions of years? And why restrict ourselves to Earth? We must also know: What went so wrong with Venus? Why did Mars become so cold? Is there life in the ocean world?

Hadn't our ancestors stepped into the unknown, we wouldn't be sitting here. Maybe we'll find another home beyond, maybe more resources, maybe the existence of another life in our celestial neighborhood. We frankly don't know but I think, stepping out and not forgetting to be kind to our own planet in the process, is the most important thing we can do for posterity.

Harvey Sapigao is a BS Physics graduate from the University of the Philippines Baguio. Follow him on twitter @hlsapigao or visit his website hlsapigao.com